What Does the Data Say - Does TPRS Really Work?

/“For the first time, my students are really engaged!…. But what about grammar?…… I love teaching again!…. I love Quizlet for online drills!….. My students are writing whole paragraphs after just three weeks!….How will they do on the AP test?…”

Many teachers tell compelling anecdotes about how TPRS has brought success in the classroom. Other teachers are not so enthusiastic. So what does the data really say? Is there any empirical research to support or oppose choosing TPRS over other teaching methods?

Actually, there is! I did a literature search. (So much easier to do these days than in the old horse and buggy times of my college years.)

Researchers Lichtman and Krashen (2013) report that “The data shows” that TPRS is more effective, or at least equal in effectiveness to other language teaching methods. And based on my own experience, I don’t distrust them. In fact, I’m inclined to believe them. But, I’m the kind of person that, if the subject is important to me, I want to see the numbers for myself. Plus, if I’m going to be teaching with TPRS, I need to be able to show the parents of my students that I am conversant with the research.

So where does one find the research papers comparing TPRS to other teaching methods? There is a website, tprsacademy.com, that lists about 70 TPRS research papers, including a bunch of comparative studies. But with ‘tprs’ right there in the name, one might think it’s a biased website. So I went straight to the horse’s mouth. Using my own library card, and my kids’ university library cards, I searched every database I could find - JSTOR, Proquest, ERIC, WorldCat and good old Google. Guess what? I found 27 comparative studies, and 24 of those studies were already on the tprsacademy.com website. So take it from me, tprsacademy.com is doing an honest and thorough job of compiling the TPRS research.

Here’s what I knew before I did my literature search. In 2014, Karen Lichtman reviewed 34 papers, including 16 quantitative studies which specifically compared TPRS to other language teaching methods. Lichtman’s review is very clear and well worth reading. In her review, Lichtman reports the specific main points that can be learned from each study, whether that be something about motivation, grammar, or speaking skills. She also has an interesting table comparing the academic successes of TPRS vs non-TPRS classes. Of the 16 comparative studies in her table, 15 show TPRS outperforming other methods in at least one measure (say, speaking). In 5 of those 15, the other method also performed better than TPRS in at least one measure (say, writing). In the sixteenth study, no significant difference was found. When a study also looked at motivation, the researcher often found that students enjoyed or preferred TPRS.*

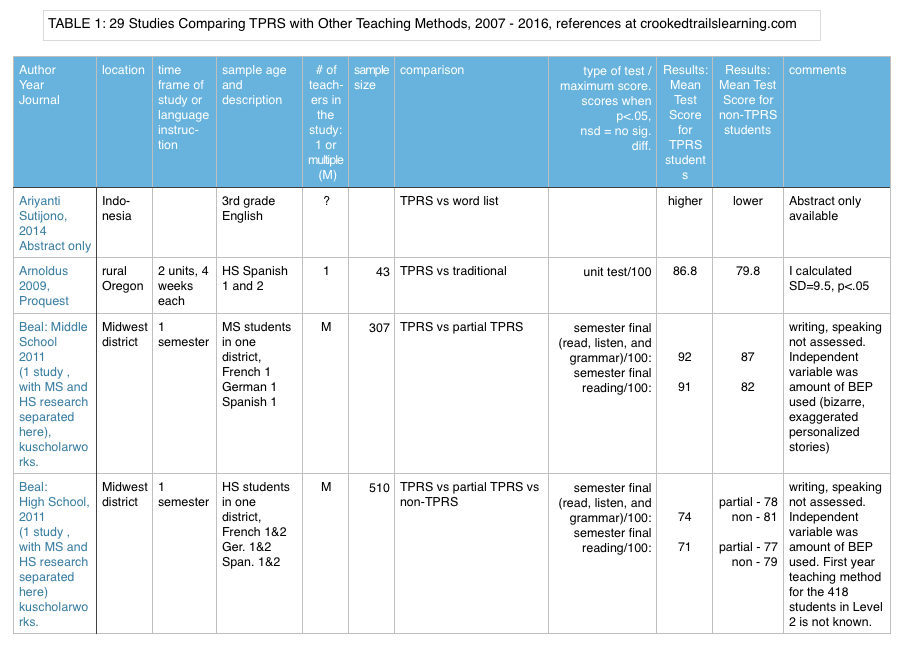

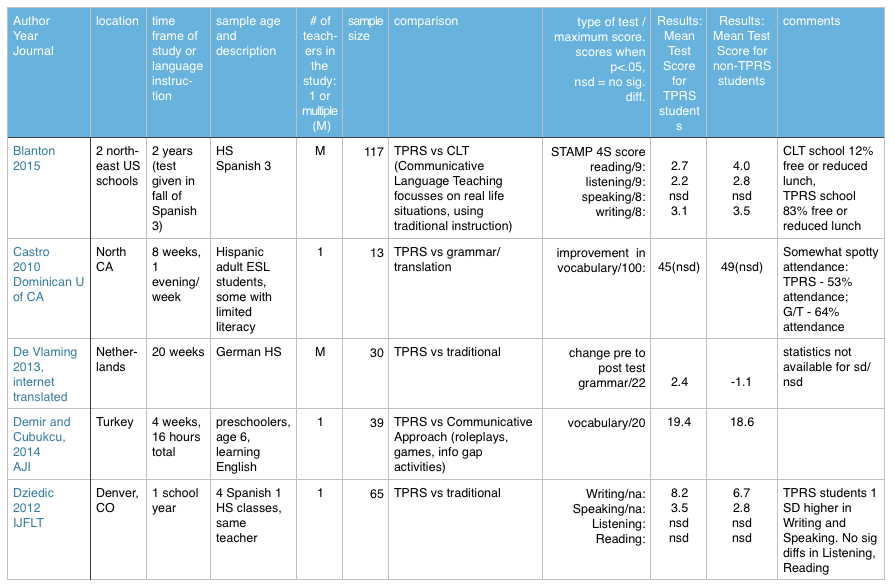

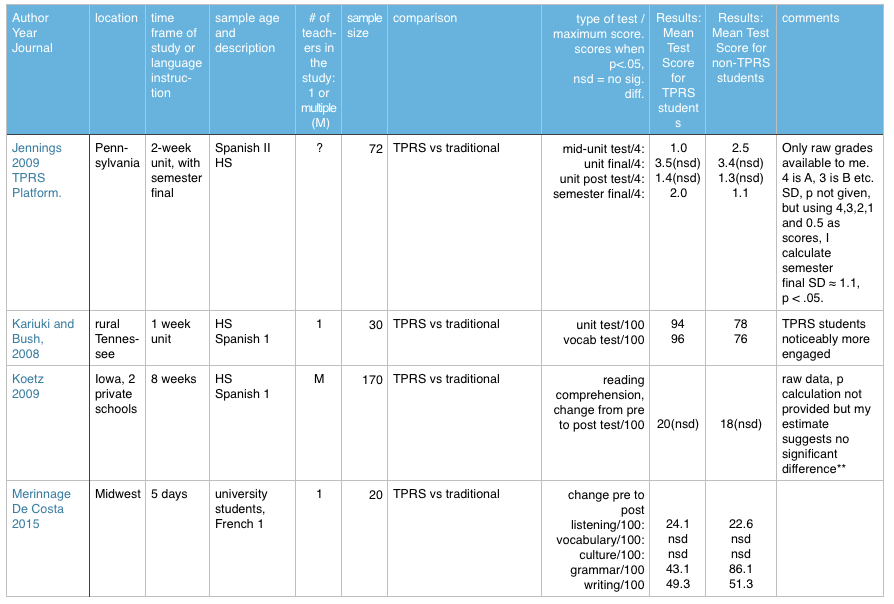

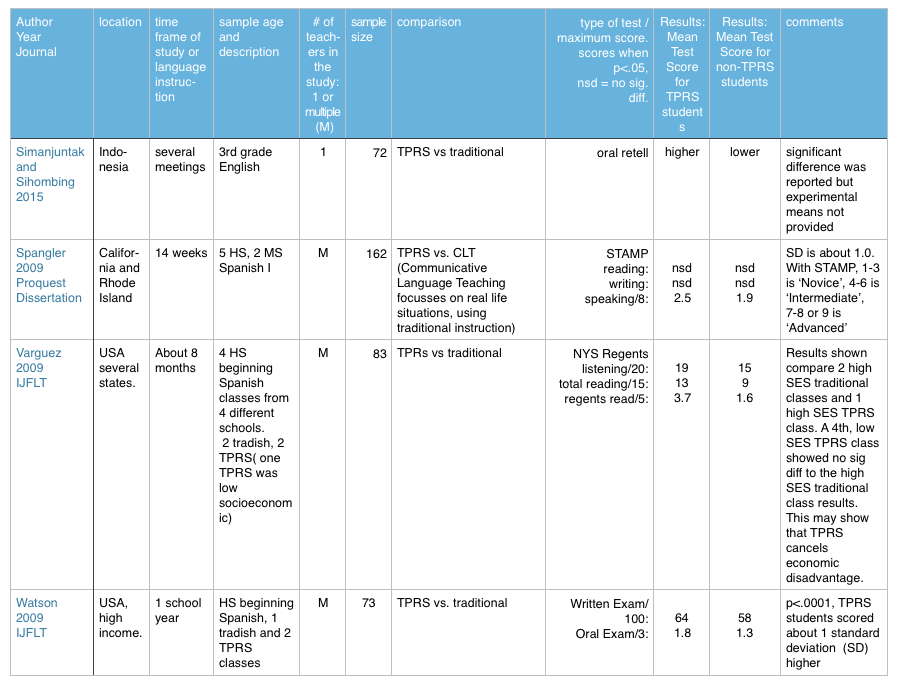

This year, in January 2017, there are more studies available, so I am able to review 27 quantitative comparison studies. To get a handle on the 27 studies, I’ve tabulated each study, with their characteristics and test results in THE WONDER TABLE. Because it is very large, I put THE WONDER TABLE at the end of this article, before the Appendix, Footnotes and References. Of, if you prefer, you can click here on THE WONDER TABLE, and open it in a separate window. The 27 studies in the table include Lichtman’s 16 studies. Most of the research done so far compares TPRS with traditional methods. A few papers compare TPRS with another specific method such as ‘CLT’ or ‘PS’. In the studies tabulated in THE WONDER TABLE, where there is a significant difference in test results between the two methods, I simply record the two means (test averages). If no significant difference exists, I note ‘nsd’.*

Any study individually could be questioned for factors that might muddy the results. For example, maybe the TPRS teacher was just better than the traditional teacher. Maybe, if there was one teacher, she was biased towards a certain method and so worked harder to teach with that method. Maybe one class was just smarter than the other class. Maybe one school was wealthier than the other (usually SES differences are mentioned in the study). Maybe one class just had a bad day on test day. However, as the number of studies increases, the muddying factors tend to cancel each other out. Therefore, you'll see in THE WONDER TABLE that I’ve also recorded many parameters for each study - year, sample size, age of students, location, language, time frame, other method studied, and whether 1 or more than one teacher was involved. In this group of research papers there is variety of studies - long and short term, single vs. multiple teachers, one school vs. multiple schools - so we can hope any muddying error factors do actually balance themselves out.

(Believe me, this is no ordinary blog. It’s taken me 2 months to get through all these dissertations and theses and articles, and figure out a way to meaningfully compare them. This blog is over the top and way too nerdy, but the cool thing is, you can check my word on everything - all these studies are available through the internet - just see the References section below and ‘click’!)

27 Comparative Studies

Well, what do the 27 studies available in 2017 show? For convenience, I divided Beal’s study into 2 studies - Middle School (MS)study and High School (HS)study. I also divided Foster’s study into two studies - short term(ST) and long term(LT). So we can say, in effect, that I am working with 29 studies. All the details are in THE WONDER TABLE, but here is an overall tally of the findings.

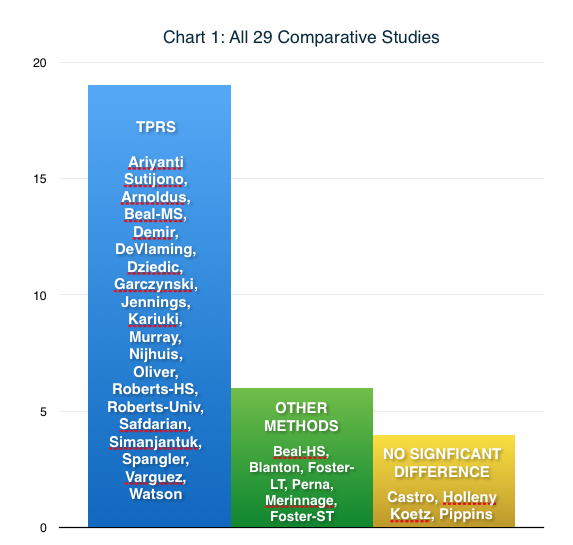

Of the 29 studies:

- 16 showed TPRS students performing significantly better

- 4 showed non-TPRS students performing significantly better

- 2 showed mixed results, but with a leaning toward the non-TPRS method

- 4 showed no significant difference between methods

- 3 reported statistically significant positive results for TPRS over another method, but I did not have access to enough data in the article to verify the standard deviation or p value.

**See the Footnote about “significant results”, below. WAY below.

Chart 1: all 29 comparison studies, grouped by which teaching method outperformed the other***

15 Long-Term Comparative Studies

Now let's remove the three studies where I did not have access to either significance data or raw data - Ariyanti Sutijono, De Vlaming, and Simantunjak. Focussing down on the remaining 26 studies, I think the most interesting studies are those which look at long-term results. The goal, after all, is some level of fluency, not good quiz grades. Many language students will show great short-term memory results after traditional grammar and translation work. But which teaching method encourages retention and fluency over the long term? Let’s look at the studies that lasted more than 32 days:

____________The Study__________________________ __Better Results?_____

- Arnoldus 8 weeks 42 HS Spanish students TPRS

- Beal - MS 1 semester 307 MS Span, Fr, Ger TPRS

- Beal - HS 1 semester 510 HS Span, FR, Ger traditional

- Blanton 2 years 117 HS Span CLT

- Dziedic 1 year 65 HS Span TPRS

- Foster - LT 10 weeks 61 HS Span PI

- Jennings 1 semester 65 HS Span TPRS

- Koetz 8 weeks 179 HS Span nsd

- Murray 6 weeks 27 HS French TPRS

- Nijhuis 6 months 32 HS French TPRS

- Oliver 1 semester 129 College Span TPRS

- Pippins 3-4 years 13 AP Span nsd

- Safdarian 1 semester 102 MS/HS Engl TPRS

- Spangler 14 weeks 162 MS/HS Span TPRS

- Varguez 8 months 83 HS Span TPRS

- Watson 1 year 73 HS Span TPRS

In chart form, the long-term list looks like this:

CHART 2: 16 long-term STUDIES, GROUPED BY WHICH TEACHING METHOD OUTPERFORMED THE OTHER

This group of long-term studies represents 1778 students, 57 teachers, 124 classes, 25 schools, 11 states and 3 countries. In the long term, TPRS performed better in 69% of the studies, and non-TPRS methods performed better in 19% of the studies. 13% (2 studies - Koetz and Pippins) showed no significant difference, but Koetz showed a small numerical difference favoring TPRS, and Pippins, the AP study, showed TPRS students performing equal to the national average on the AP test.

This is a clear “Hurrah! ¡Olé! Bravo!” for TPRS as a teaching method, and I feel very comfortable with my decision to continue using TPRS in my classroom, and with my decision to create this blog introducing homeschoolers to TPRS!

And (drum roll, please) here is the table to end all tables, THE WONDER TABLE, compiling all 29 studies! Like I said, over the top. But cool.

THE WONDER TABLE

There are of course, non-empirical reasons to recommend TPRS as the teaching method of choice for homeschool foreign language classes - student engagement, the fostering of creativity and confidence, ease of preparation, low cost of materials, adaptability to any group or language, and fun! However, in this blog I have looked at only the empirical research comparing the effectiveness of TPRS with other teaching methods. And….......

In conclusion, after a very detailed and careful review of all the available comparative, empirical research on TPRS vs. other language teaching methods, it is clear that in most cases, TPRS outperforms other teaching methods when test scores are compared. This difference is true for long-term as well as short-term studies. So, even on the basis of academic success alone, homeschoolers (and others!) can feel very confident when choosing to teach with TPRS in their foreign language classes.

Congratulations! You made it to the conclusion of a very numerical blog. If you feel like you are going to burst from statistics overload, you can stop reading now! (And thank you for staying with me all the way to the end!)

But if you haven’t yet died of numbers nimiety, or statistic satiety, or education inundation, here follows an appendix, footnotes, and references!

“APPENDIX: WHAT ABOUT THE OTHER TEACHING METHODS?”

We can learn something from the AP (nsd) study, the 3 long-term studies where another teaching method proved more effective than TPRS, and the Perna study.

In the AP ‘nsd’ study, Pippins compared the AP grades of students who had studied Spanish using TPRS vs the national cohort of AP Spanish students. 13 students in one high school had all taken Spanish in 8th grade with some grammar instruction, then solely TPRS method in Spanish 2, 3, and 4 and then in 12th grade took a typical AP Spanish class, such as that recommended on the College Board website. These 13 students averaged 3.5 on their AP scores, exactly equal to the national average that year, showing that one can study with TPRS and do well on the AP test!

In the first long term study where another teaching method produced results stronger than TPRS, Blanton compared TPRS with Communicative Language Teaching (CLT). In both school sites the students had experienced the same teaching method for 2+ years, either TPRS or CLT. The CLT students performed better on the STAMP 4S online test. In a CLT class, teachers set up communication tasks which require students to speak in the second language (L2) early on, even the first day. These tasks include things like information gap activities (Student 1 has half the info and student 2 has the other half, so they must communicate to be successful at a task like naming people in a picture) or matching proverbs (in L2) with meaning (in L2) and then acting out one of the proverbs. CLT classes also pay close attention to structure and function in the language. So TPRS vs. CLT is really a question of “compelling, comprehensible, repetitive input” vs. “equal doses of comprehensible input and output supplemented with traditional teaching”. Unlike Blanton, when Spangler and Demir compared TPRS with a communicative approach both found TPRS to be more successful. Spangler used the same STAMP 4S test, and in his study one teacher taught both the TPRS classes and the CTL classes.

Why did Blanton find CLT to be more successful? It could be that CLT worked better for that particular group of students and teachers. Also, compared to the TPRS school, Blanton’s CLT school comes from a higher socioeconomic level with many fewer students qualifying for subsidized or free lunch. More research here would be helpful.

As far as CLT goes, my own students have enjoyed information gap activities on occasion. But many CLT activities, such as “running dictation” or writing a script in small groups and acting it out, while quite fun, do not get in the same number of repetitions as a TPRS class. For that reason, my personal choice would be to use CLT only occasionally, as a change of pace - TPRS is simply more efficient at creating repetitive input. Efficiency is important in any class, but especially in the typical homeschool class which meets only once a week, for two hours.

In a second study, Foster focussed on the proper use of the verb gustar, and found that the method called Processing Instruction produced better results than TPRS. Processing Instruction is all about using explanation and drills to raise awareness of small clues like the indirect object pronoun ‘le’ in ‘le gusta’. So it is not surprising that PI proved effective when a limited grammatical structure was tested. It is interesting to note that the understanding endured for 10 weeks. However, the TPRS students did pull ahead (insignificantly) on grammar and word count, after 10 weeks.

TPRS embraces many learning styles- kinesthetic and visual with the gestures, student actors and consistent pointing to the new words, auditory with the stories, reading/writing with the graduated readings and 5-minute rewrites, and interpersonal, with the personalized questions and story asking.

In the third study, Beal’s**** High School research shows the traditional method producing better semester final grades than the TPRS method (Beal’s Middle School study shows the opposite - TPRS students performing better than non-TPRS students). Beal’s High School study was the only long-term study I reviewed where traditional methods won out over TPRS methods. In 9 other long-term studies, TPRS produced stronger academic achievement that traditional methods. One reason for the difference may be that Beal did not administer a pre-test, so scores were overall, rather than measuring improvement during the semester. Also, the study does not record what kind of method the 418 2nd year students were exposed to in their first year. In this study, Beal decided whether to identify a teacher as TPRS or traditional by asking how often a teacher used BEPs (Bizarre, Exaggerated, Personalized Stories) in the classroom. Beal suggests that Middle School students are more receptive to crazy stories than high schoolers. I did not find this to be true with my high schoolers, but it is a good practice to know your students, and create stories that will appeal to them.

Finally, Perna’s short-term study compared TPRS with a method known as Perceptual Strengths (PS), and PS performed better than TPRS on vocabulary. (The study lasted 6 weeks, but the students were tested after each one-week unit, not given an overall test after 6 or 8 weeks). Perceptual Strengths sets up learning stations that cater to different learning styles, such as visual, kinesthetic etc. Personally, I am a big fan of teaching to your child’s learning style. But there is no research showing that PS outperforms TPRS in the long term. Also, in a homeschool class, it is A LOT of work to set up 4 or 5 learning stations for a two-hour, once-a-week class. And, in a small weekly class, PS probably does not foster the same sense of shared experience and shared laughter that you can create with TPRS. Finally, it is important to note that TPRS actually does embrace many learning styles- kinesthetic and visual with the gestures, student actors and frequent pointing to words, auditory with the stories, reading/writing with the graduated readings and 5-minute rewrites, and interpersonal, with the personalized questions and story asking.

******FOOTNOTES******

*Unlike Lichtman, I chose not to review the motivation research, for three reasons.

- 1. Home school classes are generally smaller and self-selected, so motivation is not usually a big issue.

- 2. If the teaching method is fairly successful and students are doing well, successful performance itself will motivate the students.

- 3. In order to capably discuss the motivation studies, I would have to master a whole new area of research (motivation-perception-engagement-etc.), and that could take me months!……..

So I stuck with looking at academic improvement. But, if you are interested, you can read almost all of these studies on the internet, in their entirety! (See References, below.)

Also, you might note that Lichtman and I differ in our characterizations of three studies - Perna, Castro and Foster - because we looked at the studies in different ways. Lichtman evaluates each piece of the study separately, so she might give a study 3 checks, 1 in each column: “TPRS outperforms”, “Another method outperforms” and “No significant difference”. In contrast, I am a little more strict. I look at the study overall, and if 1 piece shows TPRS outperforming, but 2 pieces show the other method outperforming, than that study gets scored in the “Another method" column. In other words, I only give out 1 check per study - “TPRS”, “Another method” or “No significant difference”.

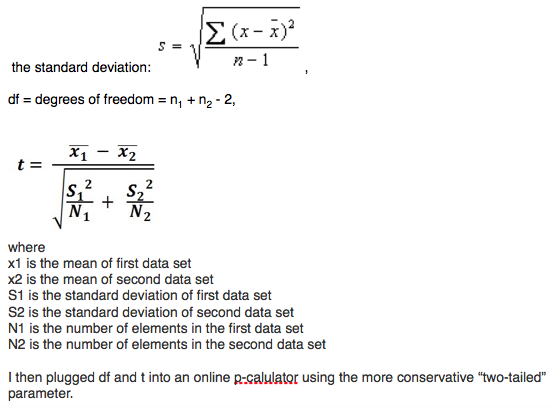

**ABOUT THE STATISTICS:

For all studies where a significant difference was found, p<.05. Remember, when a researcher says “p < 0.05” it means that there is a less than 1 in 20 chance that these results (in other words, these differences in mean test scores between TPRS and another method) would occur by random chance. Sometimes, the difference is statistically significant, but it doesn’t seem that big to us. For example, in Oliver’s research, TPRS students averaged 85% on the final, and traditional students averaged about 82%. That doesn’t seem like very much but the statistics show that this is a real, not a random difference. It may be small, but it’s real. And if you are a student, 3 points can mean the difference between a C+ and a B- on a final exam. (Remember, in school, if grades are normally distributed, 2/3rds of a class will have grades within one standard deviation of the class average or ‘class mean’. So usually, in these teaching method research studies, if there is at least one half of a standard deviation between the two means, the results turn out to be significant. This makes some sense, since in school when grading on a curve, a standard deviation is one letter grade, so half a standard deviation means something.)

If the researcher did not calculate p but did provide raw data, then I calculated p myself, using the following formulas:

*** For this graphical grouping of all the studies, I made the following decisions:

1. Jennings showed on the mid-unit test that traditional students were doing significantly better, but by the unit final that effect was erased, so for Jennings I looked only at the semester final result.

2. From the raw data presented in Murray’s paper, I recalculated the means, andcame up with 3 figures different from Murray’s. Using my (presumably correct) means, Murray’s study showed a significant difference only in speaking, where TPRS student scores dropped less (YIKES) than the traditional students, so I counted Murray under the TPRS list.

3. Roberts compared results of a 5-day language TPRS-style camp with national HS scores, and with University Spanish placement scores. Although the language campers had lower scores, when one looks at ‘points per hour’ the campers (using TPRS) learned significantly more per hour than the comparison groups, so I scored them as TPRS.

****Beal’s very large study used ten times as many students as any of the other long-term studies. This means, internally, small differences will be more significant. It’s size does not necessarily make it more important than the other studies however, because it is still one study, with whatever unique limitations that particular study design will tend to have.

R E F E R E N CE S

Almost all the articles referenced in this blog are listed on the incredibly helpful website, tprsacademy.com, under “What is TPR storytelling”, Scientific Research. Unless otherwise noted, all articles were accessed by clicking on the citation at tprsacademy.com, and most recently accessed Jan. 13, 2017. Sometimes it was easier to find the article on the Dutch version of tprsacademy, known as tprsplatform.nl. A few papers I accessed through Proquest. The only articles not listed on the tprsacademy.com website are Arnoldus (Proquest), Pippins (IJFLT) and Roberts (IJFLT).

Ariyanti Sutijono, A. (2014): The effect of Total Physical Response Storytelling (TPRS) on the vocabulary achievement of elementary school students. Bachelor’s of Education thesis. English department faculty of teacher training and education Widya Mandala Catholic University Surabaya, Indonesia.

Arnoldus, N. (2009) Methodology of Foreign Language Teaching. Master’s Thesis. Eastern Oregon University, La Grande, Oregon. Dissertation/thesis number EP75938, ProQuest document ID 1711734460, (accessed through Proquest, Jan. 2017).

Beal, K.D. (2011). The correlates of storytelling from the Teaching Proficiency through Reading and Storytelling (TPRS) method of foreign language instruction on anxiety, continued enrollment and academic success in middle and high school students. Doctoral dissertation. University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas.

Blanton, M. (2015). The effect of two foreign language teaching approaches, communicative language teaching and teaching proficiency through reading and storytelling, on motivation and proficiency for Spanish III students in high school. Doctoral Dissertation. Liberty University, Lynchburg, Virginia.

Castro, R. (2010): TPRS for Adults in the ESL Classroom: A Pilot Study Comparing Total Physical Response Storytelling™ With the Grammar-Translation Teaching Strategy to Determine Their Effectiveness in Vocabulary Acquisition Among English as a Second Language Adult Learners. Master’s thesis. Dominican University of California, San Rafael, California.

De Vlaming, E.M.(2013): TPRS in de Duitse les. Onderzoek naar de effecten van TPRS op het toepassen van grammatica. Master’s thesis. Hogeschool Arnhem Nijmegen, Nijmegen, Netherlands. Referenced at tprsacademy.com. Accessed the Dutch version of tprsacademy website, called tprsplatform.nl, clicked on “Onderzoek” (Research), found De Vlaming’s full paper in Dutch and ran it through Google Translate. Jan 13. 2017.

Demir, Ş. and Çubukçu, F.: (2014): To have or not to have TPRS for preschoolers (TPRS DİL ÖĞRETİM METODU OKUL ÖNCESİ ÖĞRENCİLERİNE UYGULANMALI MI UYGULANMAMALI MI). Asya Öğretim Dergisi [Asian Journal of Instruction], 2(1(ÖZEL),2014-2, 186-197.

Dziedzic, J. (2012). A Comparison of TPRS and Traditional Instruction, both with SSR. International Journal of Foreign Language Teaching, 7:2 (March 2012), pp. 4-7.

Foster, S.J. , Larson-Hall, J., Chelliah, S., and Vigil, D. (2011). Processing instruction and teaching proficiency through reading and storytelling: A study of input in the second language classroom. Master’s thesis. University of North Texas, Denton, Texas.

Garczinsky, M. (2010): Teaching proficiency through reading and storytelling: Are TPRS students more fluent in second language acquisition than audio lingual students? Thesis. Chapman University, Orange, California. (Proquest)

Holleny, L. (2012): The effectiveness of Total Physical Response Storytelling for language learning with special education students. Master’s thesis. Rowan University, Glassboro, New Jersey.

Jennings, J. (2009): Results of Master’s Thesis comparing two TPRS groups and one control group of Spanish ll high school students.Referenced at tprsacademy.com. The full thesis is available at Millersville University. The results data is provided on tprsplatform website, at http://www.tprsplatform.nl/?page_id=440. Accessed Jan. 13, 2017.

Kariuki, P.K.D. and E.D. Bush (2008): The effects of Total Physical Response by Storytelling and the Traditional Teaching Styles of a Foreign Language in a selected High School. Annual Conference of the Mid. South Educational Research Association Knoxville, Tennessee. (Can also get through eric)

Koetz, K.M (2009).: The effects of the TPRS Method in a Spanish l classroom. Referenced at tprsacademy.com. Morningside College, Sioux City, Iowa. Also available here: panamatesol.org/yahoo_site.../The_Effects_of_the_TPRS_Method.40144800.doc, Accessed Jan. 13, 2017.

Lichtman, K. Appendix C: Research on TPR Storytelling. Northern Illinois University. Found in the book: Ray, B. and Seeley, C. Fluency through TPR Storytelling: Achieving Real Language Acquisition in School, SeventhEdition. Command Performance Language Institute, 2015. On the internet at http://forlangs.niu.edu/~klichtman/tprs.html. You can also access it through tprsbooks.com, under ‘Free’.

Lichtman, K., and Krashen, S. "Show me the data: Research on TPRS." NTPRS 2013 (National TPR Storytelling Conference), Dallas, TX, July 25, 2013. At http://forlangs.niu.edu/~klichtman/tprs.html, Accessed Jan. 13, 2017.

Merinnage De Costa, R.S. (2015) : Traditional methods versus TPRS: Effects on introductory French students at a medium-sized public university in the Midwestern United States. All Theses, Dissertations and Other Capstone Projects. Paper 513. Master’s thesis. Minnesota State University, Mankato, Minnesota.

Murray, C. (2014): Does the Introduction of a TPR and a TPRS Teaching Method into a French 1 Classroom Positively Affect Students’ Language Acquisition And Student Appreciation of the Language? Master’s thesis. Caldwell College, Caldwell, NJ. (Proquest)

Nijhuis, R. en Vermaning, L. (2010): Onderzoek lesmethode TPRS. Bachelor of Education thesis, Fontys Hogeschool te Tilburg, Tilburg, Netherlands. Referenced at tprsacademy.com. Accessed the Dutch version of tprsacademy website, called tprsplatform.nl, clicked on “Onderzoek” (Research), found Nijhuis’ full paper in Dutch and ran it through Google Translate. Jan 13. 2017.

Oliver, J.S. (2012). Investigating storytelling methods in a beginning level college class. The Language Educator, 7:2 (February 2012), pp. 54-56.(Also available through tprsteacher.com, search ‘Oliver’)

Perna, M. (2007). Effects of Total Physical Response Storytelling versus traditional, versus initial instruction with primary-, reinforced by secondary-perceptual strengths on the vocabulary- and grammar-Italian-language achievement test scores, and the attitudes of ninth and tenth graders. Doctoral dissertation. St. John’s University, New York, NY. (Proquest)

Pippins, D. and Krashen, S. (2016). How Well do TPRS Students do on the AP? International Journal of Foreign Language Teaching, 11:1, (May 2016), pp. 25-30. WWW.IJFLT.COM.

Roberts, B. and Thomas, S. (2014). Center for Accelerated Language Acquisition (CALA) Test Scores: Another Look at the Value of Implicit Language Instruction through Comprehensible Input. International Journal of Foreign Language Teaching, 10:1 (December, 2014), pp. 2-12.

Safdarian, Z. (2012): The Effect of Stories on Young Learners' Proficiency and Motivation in Foreign Language Learning. Master’s thesis. Kharazmi University Foreign Language Department, Tehran, Iran. Published in International Journal of English and Education ISSN: 2278-4012, 2:3, (July 2013), pp. 200-248.

Simanjuntak, Y.R. and L. Sihombing (2015): The Effect of Using Total Physical Response Storytelling on Students' Speaking Achievement. Journal of English Language Teaching of FBS-Unimed, 4:2 (April-June 2015), pp. English Language and Literature Department of UNIMED, Medan State University, Medan, North Sumatra, Indonesia. Can also access this at portalgaruda.org and search by title or authors.Or go to the online journal http://jurnal.unimed.ac.id/2012/index.php/eltu/article/view/2106

Spangler, D. E. (2009). Effects of two foreign language methodologies, Communicative Language Teaching and Teaching Proficiency through Reading and Storytelling, on beginning-level students’ achievement, fluency, and anxiety. Doctoral dissertation, Walden University, Minneapolis, Minnesota. (Proquest)

Varguez, K.C. (2009). Traditional and TPR Storytelling Instruction in the Beginning High School Classroom. International Journal of Foreign Language Teaching, 5:1 (Summer 2009), pp. 2-11.

Watson, B. (2009). A comparison of TPRS and traditional foreign language instruction at the high school level. International Journal of Foreign Language Teaching, 5:1 (Summer 2009), pp. 21-24.

Many thanks to timtim.com for the worm and mouse, and unsplash.com for the elephant and waterfall!